Gladys, Reborn

(The following is a short story I wrote that won first prize at the 2015 Blue Ridge Mountains Christian Writers’ Conference)

Gladys, Reborn

Since turning twelve, she had not felt comfortable in her own skin. Bags of fat, small as a pre-teen but grotesquely defined now, dripped from her neck, stomach, and thighs, and protruded elsewhere around her body. Wearing a bikini was out of the question most days, but today she felt defiant.

Just once more, she would feel the warm sun on her skin. Feel it like she used to, as a little girl playing carefree on the beach, beneath the cries of seagulls, waves washing over ankles, sand between her toes, and the sight of her family in their sunglasses smiling and waving to her from under the big umbrella. She longed to recapture that feeling of utter JOY inside, of sunshine and sea breezes and rushing water and happiness of thinking things would always be this way.

Then the fat came, and the jokes, and the hating of herself.

She needed that childlike feeling again. Just bare skin, warmth, and sunshine. A little slice of heaven, just once more.

It would not be pleasant, enduring the stares of strangers on the cruise ship, and the muffled laughter of children that echoed like those at her middle school thirty years ago, but she owed it to herself. If this was going to be the last ‘treat’ of her life, then she was going to do it with no mind to the critics. She would put her body on display for the harsh opinions of others, but ignore them as best as she could, because she deserved that little slice of heaven before she died. And their jokes and judgmental stares would carry back with her to her cabin and give impetus to her next action, the swallowing of an entire bottle of Percocets chased with a bottle of vodka. She’d drift off and never endure another insult again.

Oh she’d tried to lose weight. Innumerable diets and exercise regimens. Meetings and online support groups. Consults with bariatric specialists. Gastric bypass surgery? Lap band? Options, but she’d heard horror stories of dead stomachs, perforations, uncontrolled vomiting, repeated surgeries to fix those problems, and with her luck, believed she would be another horror story doctors ‘had’ to tell others about when warning patients of the risks. She’d asked a family doctor if she could possibly have hypothyroidism, acromegaly, or any of a dozen other conditions that could be working to sabotage her weight loss efforts. They’d drawn blood and run an MRI.

“No,” he said seriously when the results were in, “it seems you’re perfectly fine.” other than a lack of discipline, he didn’t have to say. His smile was an attempt at empathy, but she remembered it as a smirk.

His unspoken verdict was she was fat because she just wanted to be. Couldn’t cut off the ‘mouth valve’, the appetite that equaled an addict’s need for heroin, and whose euphoric satisfaction upon its sating was every bit as fulfilling.

Trembling, she doffed her clothes and donned the bikini.

And a large beach towel, which she would remove only once reclined in the sun-bed, as the fabric of the lower part of the swimsuit was swallowed into her generous folds making her appear unclothed from the front.

A worry passed through her about how well the lounge chairs on deck might support a gal of her size. She’d had several embarrassing incidents with furniture. Perhaps she should skip the final parade of shame and just swallow the pills now. Tears burned and fists clenched. No, she was not going out before taking in the last treat. She had a date with a pleasant childhood memory and she would keep it.

She slid into her flip flops and trudged into the hallway. Keeping her head down she made it to the elevator and pressed the button for the second deck. A couple approached before the door closed, surveyed the room left in the car, and wordlessly decided to take the stairs.

Gladys stood in the shadows by the elevator once on second deck and surveyed her options, looking for a sturdy chair in the sun but near by, to limit the time she had to parade her body in front of others. The arrival of a new person on deck would naturally attract stares, and they would linger, subtle smiles would form, heads would shake, children would be ordered not to stare but they would. And they’d laugh.

God was being kind today because she spied a good spot a short distance away and was soon settled in its embrace, the scent of cocoa butter still on the plastic from the last sunbather. The webbing creaked as the bands accommodated her form. She felt the warmth of the deck on her backside and realized the seat had let her sink all the way to the floor. She deftly draped the towel over her to conceal that fact and provide a little privacy over her front. She’d remove it in a few minutes once people were tired of staring.

The warm air blew gently across her skin and between her toes. The aroma of sunshine on the salt water was delicious. Her memories returned her to those pleasant moments on various beaches of her childhood with her laughing, happy family.

What would they feel when they learned of her death? Certainly not surprise. The Captain or another officer, maybe a chaplain, would call ship-to-shore informing headquarters, or maybe call her family directly. It would be a task getting her corpse off the ship but that wasn’t her problem. There was even a little morgue on board, used for frozen foods until and unless it was needed for a body. Then the food would be cooked, thawed in refrigerators, or thrown out, unless nobody knew it had shared space with a corpse, in which case her fellow passengers would be blissfully unaware as they gobbled their buffets.

A buffet sounded good right now actually.

A waiter came by offering drinks and a small assortment of snacks. She took a piña colada and some cookies. Then another fistful of cookies. A seagull called to her for the last time.

Arrangements would have to be made regarding her remains. She chuckled at that. Such an absurd euphemism. A hearse would be hired to meet the ship once in port. Perhaps the cruise line would cover that expense as a final courtesy, seeing how she didn’t eat her share of food for the last few days of the cruise. An autopsy would be ordered to relieve the cruise line from any liability. And to their relief it would show she’d overdosed and not been murdered or contracted botulism from her dinner.

She dozed lightly in a balmy reverie, blissful in the sun, bathed in the warm breeze and the gentle soporific effect of the cocktail.

Gladys woke to a gradual crescendo of distant screams from other decks, which eventually infected her level as well. She’d felt a concussion perhaps but disregarded it as an engine noise, or some other necessary mechanical thing of ships. Smoke now rose over the railing, scant at first, then black and rolling. More screams and scuttling now of passengers here and there. A stern command from the speakers in an authoritarian voice, that all passengers must don life vests and stay calm.

Parents cried for children who cried back, all running around to find each other. Gladys stayed put for now, thinking how much trouble it would be to roll to her knees, stand (eventually) by pressing on the cot for support, trundling around like the others, just to hear an ‘all clear’ a moment later after someone found a fire extinguisher. She’d had middle-of-the-night fire alarms at hotels that had gone just that way. Too much effort to expend for what was probably just a false alarm.

Moments later, a wide eyed steward made it to her deck to inform her that the ship was indeed sinking, due to an explosion in the engine room that ruptured a hole through the bulkhead and hull beneath the water line, and all must proceed to life boats immediately. He found a life jacket and brought it to her, then brought a second one saying only ‘last one’.

Okay, this was a bit more urgent now. She’d planned on taking her life peacefully, under the power of the oxycodone, not drowning, struggling for breath. The steward had disappeared, so she wrestled the life vests around her saggy arms, clicking their clasps together in the front. She could not reach her back, so she took the jackets off, fastened them in the back first in double-wide fashion, donned them again, then snapped them together in the front. Each vest would float about a hundred-eighty pounds of human, so the label said. A third would be helpful.

Now on her knees, she pushed mightily downward on the sun-bed to help her rise. The cot flipped over to that side in response. Cursing, she righted the cot and scuffled on her knees to the foot end, pressed down again with her arms and strained with her legs. The head of the cot rose this time, but did not flip end-over-end. And so she stood finally, face red, chest heaving, the head end slamming back to the deck once her weight was released. A small victory, one that brought a smile.

The smoke was thicker now, spreading along her deck as a dark gray fog. Shouts of names persisted, mixing with the urgent calls from the PA and yells from staff members, creating an unintelligible cacophony. The elevators would not be working she realized, not in such an emergency. That meant stairs.

Now she could tell that the ship was listing slightly to starboard. She’d learned that much nautical terminology – port was left, starboard was right, the bow was in front, the stern in the rear. The galley was the kitchen of course. And Davy Jones’ Locker was the deep down sea where this boat was headed.

Stairs were going to be a problem. She made her way to the top of the companionway that led to the deck below and braced herself between the steel banisters, a hand on each rail. No one would be coming up, so no worries there. She took a hesitant step downward, landing successfully. Maintaining balance, she brought her other foot down to join it, proceeding one step at a time like that until she’d made it halfway.

Her left leg trembled uncontrollably with the next step, then buckled. Her body collapsed mercilessly downward, her left knee taking it hard. Momentum tumbled her forward, rolling her sideways along her back until she was face up on the landing below. Panicked wails erupted unbidden from her throat. Incapacitated, like a flailing June-bug, she struggled to find anything to grasp, anything for support.

No one was coming. No one could hear her. Even if they could, how could they help? She pressed down on the floor with her elbows as if doing a sit-up. Sweat dripped from her chins. Body trembling, she quickly abandoned this effort. They’d need ropes, a front-end loader maybe. She was pathetically, helplessly stuck here. She called out for help again and again, hoping for at least some company to comfort her. Maybe someone could go get another someone, and they’d figure out what to do.

Too late. Water was rushing up the stairs below. Fear gave her power to call out louder, a scream now, but useless. Water crested the landing, soaking her down her back, cold on her skin. She wondered how it would feel when she couldn’t hold her breath any longer, and all that sea sucked into her lungs. Would it hurt? She’d heard that drowning was peaceful and painless, but how could that be? Who had lived to give that report? After the panicked thrashing and diaphragm spasms, perhaps she’d just lose consciousness. She wished for her bottle of Percocets right now – she could down the whole thing with a swallow of salt water, and as long as she didn’t vomit, they’d take effect fairly quickly. An average person would take one or two for a normal dose. She’d need three to six for the same effect, possibly fifteen to two dozen to slip into unconsciousness and drown without knowing it.

Why was she even calculating it? No way to get back to her room anyway. Just something to occupy the mind as death approached she supposed. But it was water that was approaching and she suddenly remembered two things:

Fat floats, and salt water is buoyant.

She’d heard that people could lie on the Salt Lake in Utah without floats sometimes and just smile and splash around without a care. And suddenly she felt very blessed to have an abundance of a life saving resource wrapping her bones.

As the water covered the landing, then her legs and shoulders, she felt her body start to rise. The life vests would help some and her adipose would do the rest. There was no need to even try to stand.

As predicted, she felt her body floating, and she used her hands to steady herself as she floated head first back up the stairs. In twenty minutes she found herself at the top again.

Water covered the deck here now, sloshing the chairs around, and carrying with it a grand assortment of litter. It was soon easy to propel herself with her hands, and she slowly scooted her body towards the rail.

The six girls had kept their private playroom a secret from the adults and other kids. Situated on the fifth deck, just above the bridge, the unlocked small room was likely meant to serve as an extra berth for crew, but upon its discovery by the children, soon turned into a rumpus room, a Promised Land of freedom. They met there daily just before late lunch and giggled over their shared secret. The bed became a trampoline, they accessed whatever channels they wanted on the television, and for that hour every afternoon, they reveled in the lack of parental supervision and the feeling of getting away with mischief. They created a code to use when referring to the room and for the various things they found to do there, allowing them to discuss their secret with more giggles while adults were around. The adventure of the secret room, and their blossoming friendships, were as thrilling as any of the other entertainments on board.

Sarah, the oldest, was the first to sense something amiss. She stopped playing and listened intently at the sound of footsteps rushing down the hall. After a long moment of silence from beyond the door, she ventured out, the others following. A shout from her brought screams from the others as they made it to the outer passageway and surveyed what was happening below. Panicked, Sarah struggled to recall the safety meeting they’d had to attend. Something about a ‘muster station’. She’d been too excited to pay attention.

The ship was sinking, listing now, threatening to gently dump them over the railing. The girls held hands, screamed for their mothers, and wailed loudly. Surely someone would hear them and lead them to the lifeboats, right? Sarah could already see some bobbing in the sea. She waved frantically to them as did the others.

“We have to go down to get to the lifeboats.”

She led her sobbing friends down the companionway all the way to the second deck, which was just getting submerged. There was no one around, except one lady lying on her back.

Gladys noticed the red, wet, terrified faces of the girls as they descended the stairs and landed on her deck. Oh dear. Everyone had found a boat and fled by now for sure. And they’d all left these girls behind in the confusion. Their parents probably assumed they’d been helped to a lifeboat by the crew and would reunite once in safety.

“Where are the lifeboats?” One called to her in a shaky voice. Gladys could not reply in a voice they could hear, so just waved them over to her.

They balanced their feet precariously in the current, and slowly made it to her, hand in hand, wading in knee-level seawater.

“There aren’t any life vests or life boats left honey. So you’ll have to hang on to me.” A puzzled look came over their faces as they briefly considered alternatives.

“It’s okay – all of you just stay together, and space yourselves out around me, and hold on tight. I float well.” They were the same ages as the girls who tormented her so in school. She quashed the memory.

“Everyone get a good hold somewhere – grab on to my legs and shoulders. Just let me be able to move below my knees and elbows so I can swim us around some. Go ahead, we’re all going to get through this together.”

And they did. Using her body as a raft, they kicked gently to get away from the sinking ship. She spoke to them calmly, asking their names, encouraging them to talk about themselves. Shivering at first, they relaxed, became chatty and cheerful. She told jokes and they laughed, bouncing as one with the waves.

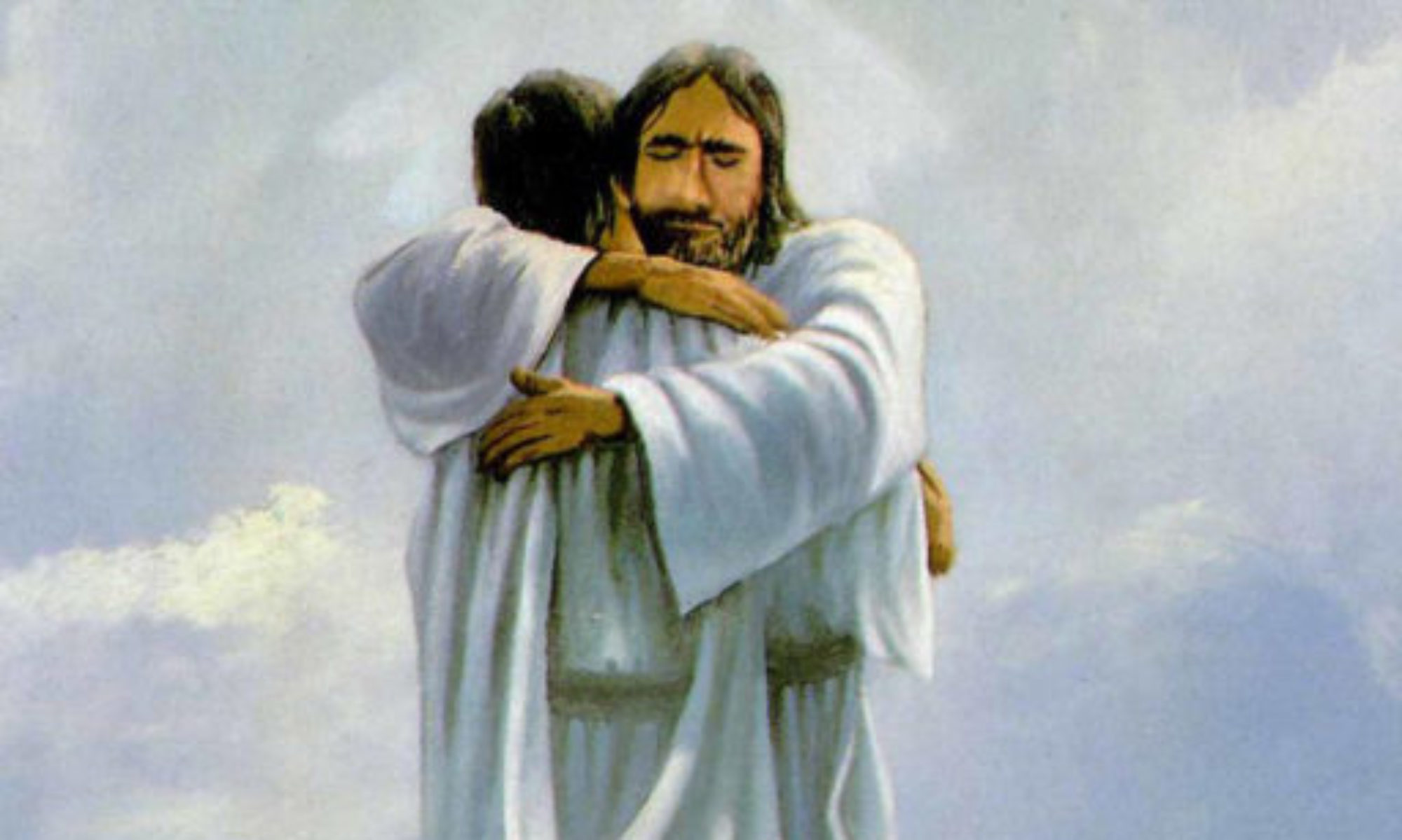

Sun on her skin, a serene smile on her face, the six scared children clinging to her, she quietly made her peace with God and her past. It mattered that she had lived. What no longer mattered were all the names meant to shame her, the lifetime suffering contemptuous stares. She spoke in her mind to the children who had teased her. Judge me anyway you want, but these children are going to live because of me. A powerful feeling of forgiveness overcame her anger.

And when the men on a boat finally pulled them to safety, the children thanked her. And hugged her tightly.

Gladys’ joy had returned.